Paula Larsson, University of Oxford

Self-isolation. Quaratine. Lockdown. The outbreak of COVID-19 and its subsequent dissemination across the globe has left a shock wave of disbelief and confusion in many countries.

Accompanying this wave has been a spike in racist terms, memes and news articles targeting Asian communities in North America. Asian Americans report being spit on, yelled at, even threatened in the streets. There has been a recent stabbing in Montréal and increased violent targeting of Asian businesses. Asian Americans reported over 650 racist attacks last week according to the Asian Pacific Policy and Planning Council. These incidents demonstrate rising racism against Asian communities in North America.

History tells us this is not the first time that fear of disease has led to outbreaks of anti-Asian racism. Underlying prejudice against Asian communities has been a staple feature of North American society since the first Chinese workers arrived in the mid-19th century.

Looking back at these outbreaks of discrimination is a sobering lesson of the consequences of racial labels for disease.

Increased racist rhetoric by politicians, like President Donald Trump’s erroneous use of the term “China Virus” for COVID-19, is often the first step to racialized violence. Trump recently agreed to stop using the racist label, acknowledging in series of tweets (@realDonaldTrump): “It is very important that we totally protect our Asian American community in the United States … the spreading of the Virus … is NOT their fault in any way, shape, or form.”

But more than 100 years ago, white spokespeople in North America had labelled Chinese people as “dangerous to the white,” living in “most unhealthy conditions” with a “standard of morality immeasurably below ours.”

Since then, white settler resentment of Chinese presence has consistently boiled over into outright racism and violence. Seminal work by Peter S. Li, professor emeritus of sociology at the University of Saskatchewan, highlights such incidences throughout Canada’s history, while historian Roger Daniels explores the rise of anti-Asian movements within the United States.

Indispensable Chinese labour

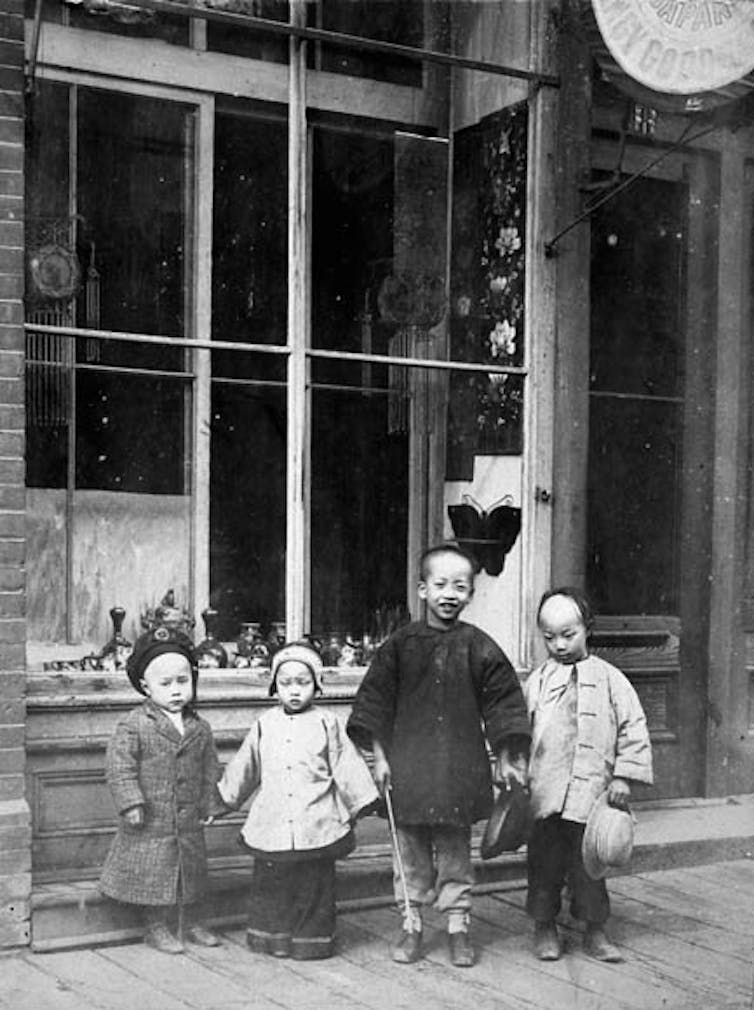

The gold rush of the mid-19th century attracted many prospectors to the West Coast of North America. Chinese immigrants arrived alongside those from Japan, the United Kingdom, Europe and elsewhere. Although the majority of prospectors travelled south to California, large prospecting encampments developed in British Columbia.

When B.C. joined Canadian Confederation in 1871, the Canadian government initiated a system to recruit and attract Chinese labour to supplement the growing requirements of building the Canadian Pacific Railway. Thousands of Chinese workers were hired and arrived by boat.

Many factors contributed to their departure from China, but in Canada, they were indispensable workers that helped complete the railroad, working at minimal pay compared to their white counterparts. Indeed, the fact that Chinese workers could be exploited for cheap labour was exactly why Canada’s first prime minster, John A. Macdonald encouraged Chinese immigration.

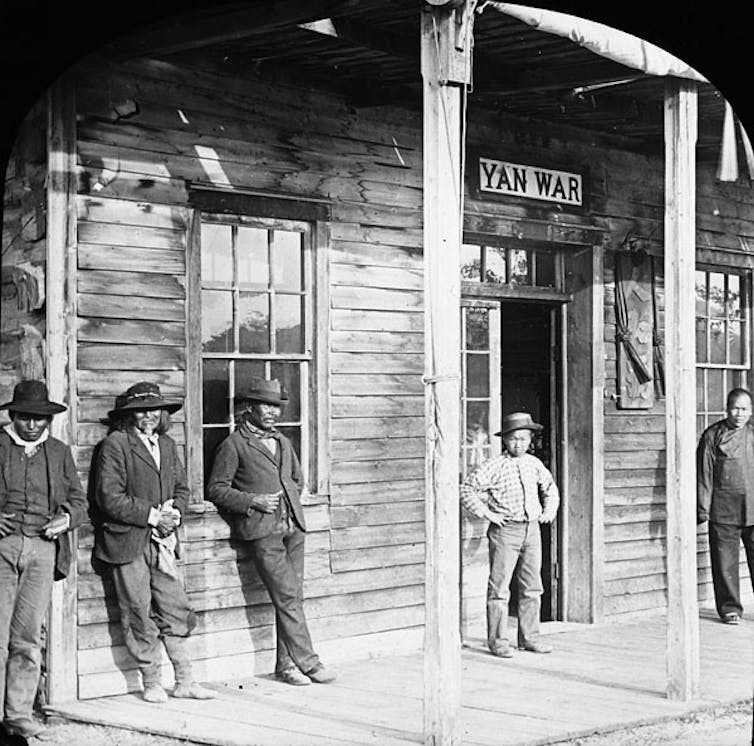

Chinese communities thrived in the growing cities of the West Coast, setting up businesses and finding employment in laundries, grocers and labour camps, as well as in domestic service, especially as cooks.

The railway was completed in 1885, seemingly ending the continued need for good but cheap Chinese labour.

The rise of anti-Asian racism

Around this time, white communities were growing disgruntled at the presence of Asian settlers in the cities. In 1880, the Anti-Chinese Association of Victoria submitted a petition to Ottawa against “the terrible evil of Mongolian usurpation” in Canada. The 1882 passage of the Chinese Exclusion Act in the United States soon led Canadian officials to consider similar measures.

In 1884, the Royal Commission on Chinese Immigration was established, to determine the impact of Chinese presence in Canada. The commission held hearings in British Columbia, San Francisco and Portland, to gather evidence from witnesses — over fifty people from among from the police, government, physicians and the public. Only two of the witnesses were Chinese.

The witness accounts reveal how underlying race prejudice has long formed the basis of North American attitudes towards China.

Blame for disease

The Royal Commission report concluded: “The “Chinese quarters are the filthiest and most disgusting places in Victoria, overcrowded hotbeds of disease and vice, disseminating fever and polluting the air all around.”

Yet the commissioners were aware that such conditions were derived from poverty, and that the overcrowded slums could occur just as easily among “any other race” that was similarly impoverished.

Despite this, both the public and many politicians continued to connect disease with race.

The Chinese were consistently accused of being carriers of infection. In the Royal Commission report, it was a common belief that syphilis, leprosy and especially smallpox were “communicated to the Indians and the white population” from Chinese communities. This despite the fact that at the time China legally required inoculation for all its citizens, and the physicians interviewed by the commission declared having “never seen a case of leprosy amongst them.”

By 1885, Canada had passed the Chinese Immigration Act which placed a “head tax” on all Chinese immigrants.

Quarantine officers at the ports were ordered to inspect all on board of Chinese origin, stripping down and examining any Chinese person suspected to be sick. Over the next 20 years, recurring smallpox epidemics were erroneously blamed on Chinese communities.

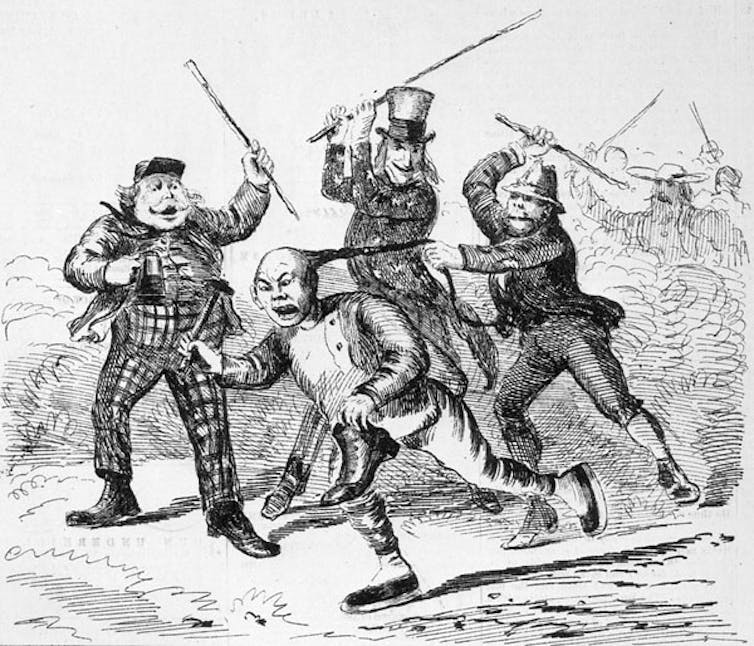

Such sentiments were accompanied by violence. In 1886, anti-Asian riots broke out in Vancouver, resulting in violent attacks on Asian workers. Similar riots occurred again in 1907, after the formation of a Canadian branch of the American Asiatic Exclusion League in Vancouver. The group organized public, inflammatory speeches against the “filth” of British Columbia’s Asian residents. On Sept. 7, 1907, a mob violently attacked Asian shops and homes in Vancouver’s Chinese and Japanese quarters.

These historical incidents of discrimination clearly demonstrate how the language of disease is often encoded with underlying racial prejudice.

“Viruses know no borders and they don’t care about your ethnicity or the colour of your skin or how much money you have in the bank,” said Dr. Mike Ryan, executive director of the World Health Organization’s health emergencies program.

Yet language can easily spark discrimination in times of fear, with dire consequences.

Paula Larsson, Doctoral Student, Centre for the History of Science, Medicine, and Technology, University of Oxford

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.