Arash Javanbakht, Wayne State University

The COVID-19 pandemic is different from many crises in that it has affected all of us regardless of politics, economics, religion, age or nationality. This virus is a good reminder that humanity is vulnerable to what nature throws at us, and that we are all in this together.

I am an academic psychiatrist specializing in research and treatment of anxiety and stress. Believe me, you are not alone if you feel like complaining.

COVID-19 has affected us if not infected us

This pandemic has profoundly changed our way of living. Overnight, dining out, exercising at the gym or seeing friends in person became impossible for millions of Americans. Remote working, reduced work hours and income, and uncertainty are indeed stressful. Most of us are having to make important adjustments and quickly learn new skills, such as how to do virtual meetings or be motivated to work from home. Given we are creatures of habit, these adjustments can be hard.

We are also stressed by continuous exposure to sad news, often contradictory predictions and recommendations coming from different sources. The constantly changing and evolving nature of this situation is very frustrating.

We humans hate the unknown and limited sense of control over life. Worse, our fear system is designed for fending off dangers, not for modern life crises where we do not need to fight or escape a predator. Hence, we need to find creative ways of responding to crisis, some adaptive and some not.

Complaining and venting

Humans are a social species, which means sharing one’s thoughts, feelings and experiences. Successful social connection involves the ability to share both positive and negative emotions. During crisis, we can get comfort in sharing our fears and receiving calming and objective feedback from others.

The question is: How much can I complain without being the person everybody avoids? We don’t want to be an Eeyore.

To answer this question, consider what we and others get out of such communication. Is the end result for us feeling less worried or sad, and others feeling supportive? Or are both parties emotionally exhausted and feeling worse?

Benefits of venting

Venting our fears and concerns can be beneficial. Sharing feelings with others, just the act of verbalizing those feelings will reduce their intensity.

Others may provide support and care, and soothe the negative feelings. And we can do the same for them. We learn that we are not alone in this, when we hear others are also having those feelings.

And, we may learn from others, how they cope with their frustration or fear, and that can help us adopt those methods in our life.

When to know the limits

Venting should not become a habit, though. At the end of the day, it won’t fix the problem. Here are suggestions on when to stop sharing negative emotions:

- When venting becomes the main coping style, and importantly, when it delays adaptive necessary action. Venting about homeschooling children will not take care of their education.

- When sharing with others stresses them. It is unfair to make myself feel better at the expense of others’ sanity. When people start avoiding you in response to your venting, it means you are stressing them out.

- When venting does not achieve the goal of feeling better, and one or both of us feel worse. Do not vent just for the purpose of complaining. Your mind is like your stomach: If you feed it good food, you will be healthy and happy. If you keep feeding it garbage, you will feel sick.

- Young children are not there to listen to our problems, and their job is not to soothe us. Being parents’ therapist can have negative long-term effects on children, the least of which is that they may learn that complaining as a main coping style.

- When you experience signs of clinical depression (depressed mood, low energy, poor or increased appetite, insomnia, poor concentration, among others), talk to your doctor to see if you need professional care beyond just a listening ear.

Other ways to cope

Here are a few tips on how to cope with the stress of these days:

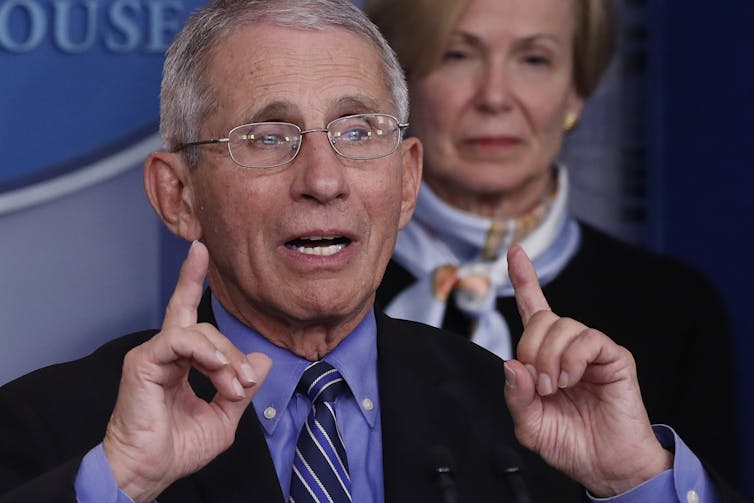

- Get your facts from medical experts, and websites such as the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and local health authorities, not from rumors or random social media posts. By knowing the facts, you get an objective estimate of the risks. Knowing legitimate ways of protecting yourself and your loved ones provides a sense of control and reduces anxiety. Just know enough to protect yourself and your family.

- Do not get obsessed with the news, and do not keep checking for hours and hours. Make sure to give yourself hourslong breaks from the news. Don’t worry – the network anchors will always be there for you to come back to them.

- Give yourself a chance to be distracted from bad news. Watch movies or TV series, documentaries (animals are awesome), or comedies if you want to watch something.

- Remember all the activities you always wanted to do but did not have time. This does not have to always be errands or housework. It could, and should, include fun activities and hobbies.

- Keep your routines. Go to bed and leave bed at the same times you did before, and eat your normal meals. Now you can spend more time cooking and eating healthy.

- If you are a social person, stay connected via phone, video chat or other technology. Physical isolation should not lead to social isolation. Connect, especially now that you have free time.

- Stay physically active. Regular exercise, especially moderate cardio, not only improves physical health and immune system but also helps with depression and anxiety. Trainers are offering free home exercise training these days online. You can also use exercise as a means for bonding with your loved ones.

- Meditate and use mindfulness techniques.

- Work on your yard or gardening projects. You will be safe, active and productive.

Finally, know that this too shall pass. Medicine will ultimately control the pandemic. We are a very resilient species and have been around for millions of years. We can survive this with wisdom.

[You need to understand the coronavirus pandemic, and we can help. Read our newsletter.]

Arash Javanbakht, Assistant Professor of Psychiatry, Wayne State University

La version originale de cet article a été publiée sur La Conversation.