Jerome Gessaroli, British Columbia Institute of Technology

The federal and provincial governments have announced massive emergency spending measures to ease the financial hardships many Canadians are facing due to the COVID-19 pandemic.

Quick and significant spending is required. However, both levels of government will have to borrow heavily to pay for this financial support.

Numbers from the independent Parliamentary Budget Office point to a 2021 federal budget deficit of $90 billion more than originally forecast, while the three largest provinces will be providing upwards of $25 billion dollars in additional assistance.

Prime Minister Justin Trudeau recently offered reassurances to Canadians that the federal government is fiscally on form to help people and businesses hit hard by the pandemic.

Trudeau said “we are in an enviable position of having significant fiscal firepower available to support you.” He subsequently stated that “we are the G7 country with the lowest debt-to-GDP ratio,” suggesting that Canada can borrow as planned without it stressing our future fiscal position.

Two critical questions

There are two key questions to answer regarding our country’s fiscal sustainability when it comes to dealing with this black swan moment, which is defined as an unpredictable event with potentially profound consequences.

What is our ability to provide short-term meaningful financial support to Canadians in need? And how quickly will our economy recover when robust economic activity resumes, allowing people to be hired and profits to be taxed?

Using 2018 data from the International Monetary Fund, we can compare how Canada ranks in terms of the federal government’s debt-to-GDP ratio. The graph shows that federal government debt in proportion to our economic size is the lowest of the G7, though not Australia, which is comparably sized but not in the G7. At first glance, it suggests that Canada has greater relative borrowing capacity in a time of need.

The above data, however, only explains the country’s fiscal debt load at the federal level. Provincial governments also borrow to cover their spending needs. Though each province is responsible for covering its own debt and interest, the fact is the federal government would very likely have to assume responsibility if any province could not meet their financial obligations.

That being the case, to get a better picture of how much debt our governments owe, and how much borrowing capacity we have relative to others, we need to also account for provincial debt.

A troubling picture

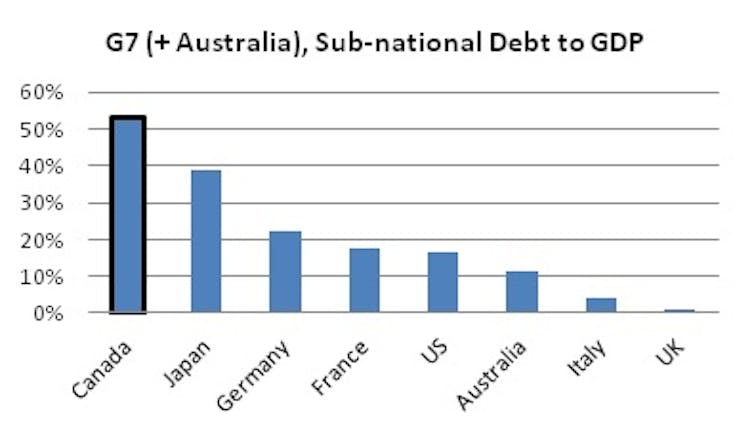

And here the picture is more troubling. Government borrowing, at the provincial (and municipal levels), is by far the highest of the G7 plus Australia.

If the federal government is considered the final guarantor for provincial debt, then our fiscal position is not nearly as strong as suggested by our prime minister. Fitch, a major credit rating agency, considers both provincial and federal debt in their credit assessment. Based on pre-pandemic economic forecasts, Fitch writes that Canada’s federal and sub-national (mainly provincial) debt “is higher than other AAA-rated sovereigns … and remains close to a level that is incompatible with AAA status.”

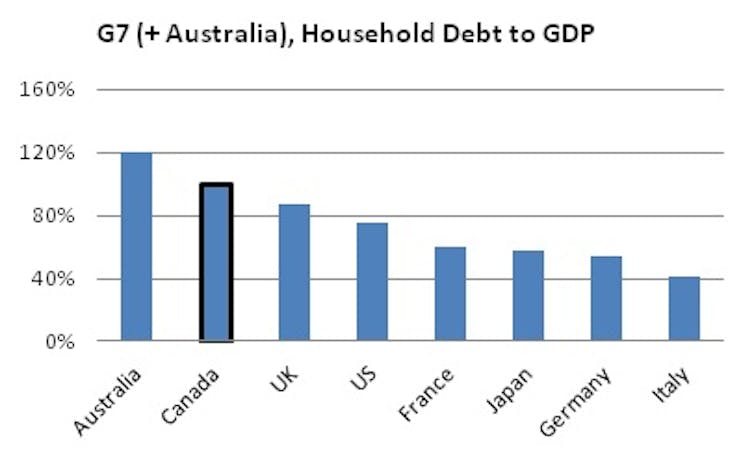

The third element we should consider is household debt. If households have their own “fiscal firepower,” they can self-sustain in troubled times without massive government spending.

The graph below compares the amount of debt Canadian households carry compared to G7 and Australian households. We have the highest household debt levels after Australia. Unfortunately, high household borrowing results in high fixed borrowing costs. When combined with a sudden job loss, this can lead to financial ruin.

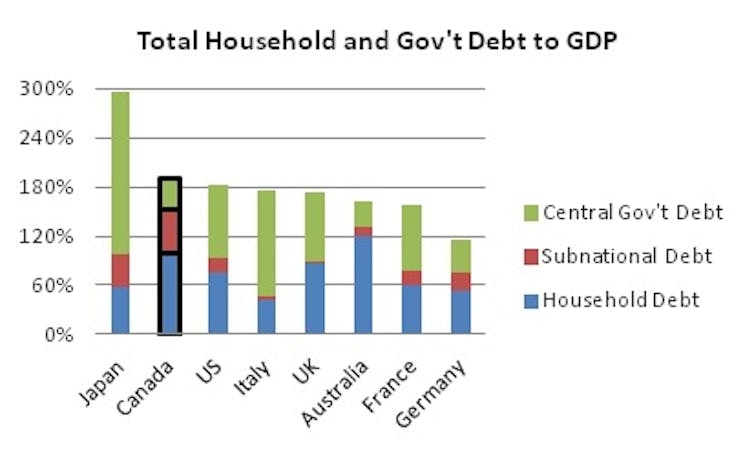

To complete the picture, let’s compare Canada’s level of federal, provincial and household borrowing to the G7 plus Australia. Canada places second-highest, behind Japan, for overall indebtedness relative to economic size. In fact, Canada ranks worse than Italy for overall indebtedness. The data suggests that borrowing levels, both by government and households, are currently high.

Some may argue that the federal government is technically not responsible for provincial debt. That may be the case. However, history appears to support the federal government bailing out provinces in the past.

In 1936, the province of Alberta defaulted on $42 million of its provincial debt, only later to be bailed out by Ottawa.

Around the same time, Ottawa also bailed out Saskatchewan just before they defaulted. Saskatchewan again came close to defaulting in 1993 before the federal government rushed to give financial support to the province.

In a paper on provincial and municipal borrowing, economics professors Richard Bird and Almos Tassonyi wrote that “… the federal government appeared to have rendered itself implicitly liable for all provincial debt.”

More recently, Walter Schroeder, the founder of credit rating agency Dominion Bond Rating Service, mused that “the easiest call I’d ever have to make as a debt rater would be a Newfoundland bankruptcy. It’s a sure thing.”

In fact, on March 20, Newfoundland and Labrador Premier Dwight Ball wrote in a letter to Trudeau that “… attempts to finalize our borrowing program, both short term and long term, have been unsuccessful.” The Bank of Canada subsequently agreed to buy the province’s bonds so they could continue to borrow.

The need to put money into peoples’ hands due to massive job losses is real and necessary.

While Canada currently has the borrowing capacity to lessen the financial pain from COVID-19, our day of fiscal reckoning is coming, sooner rather than later. A tipping point will be reached and governments and individuals will be forced to take measures that will be both personally and politically unappealing.

Our future could consist of credit downgrades by rating agencies that will result in us having to pay higher interest rates on our debt. Canadians will also face higher taxes and a reduction of government programs to shrink our over-leveraged position.

Planning for black swan events

Unfortunately, if the economic recovery takes some time, the government’s ability to provide further support programs to affected Canadians will be significantly limited.

When the pandemic passes, finance officials at the federal, provincial and municipal levels will all have to objectively reconsider our debt policies, including budgetary deficits and program and statutory spending. Regular budgetary planning will have to include possible black swan events.

Just as the government maintains national stocks of medical supplies to draw upon in times of an emergency, Canada must build a reserve borrowing capacity — meaning the ability to borrow in times of crisis while avoiding a painful debt hangover, post-crisis.

All three levels of government must prioritize reducing the country’s level of indebtedness.

Canada will face future economic shocks, whether through pandemics, natural disasters or economic recessions. While such events may incur unavoidable human costs, the government will be in a position to offer meaningful economic support to those most affected while still allowing the economy to recover as quickly as possible.

Jerome Gessaroli, Faculty, Financial Management, School of Business, British Columbia Institute of Technology

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.