Stanley Shanapinda, La Trobe University

A conspiracy theory claiming 5G can spread the coronavirus is making the rounds on social media. The myth supposedly gained traction when a Belgian doctor linked the “dangers” of 5G technology to the virus during an interview in January.

Closer to home, Facebook group Stop5G Australia (with more than 31,700 members) has various posts linking the disease’s spread to 5G technology.

Peddling such misinformation is not only wrong, it’s destructive.

The Guardian reported that since Thursday at least 20 mobile phone masts across the UK have been torched or otherwise vandalised. Mobile network representative MobileUK published an open letter stating:

We have experienced cases of vandals setting fire to mobile masts, disrupting critical infrastructure and spreading false information suggesting a connection between 5G and the COVID-19 pandemic.

Celebrities – stick to what you know

Many outlets and people have rushed to debunk this myth, including federal minister for communications, cyber safety and the arts Paul Fletcher. But myriad groups and public figures continue to perpetuate it.

Actor Woody Harrelson and singer Keri Hilson have both shared content with fans suggesting a link between 5G and COVID-19.

Stop5G Australia members have claimed the Ruby Princess cruiseliner’s link to 600 reported infections and 11 deaths is because cruises are “radiation saturated”. That’s wrong.

While cruise passengers can access roaming wifi services on board, these are not 5G services. Maritime cruises have yet to implement 5G technology.

One petition is calling on the Australia government to stop 5G’s rollout because the technology can supposedly “negatively affect your immune system” (a claim for which there is exactly zero evidence). It has received more than 27,000 signatures.

How 5G radio signals (radiation) work

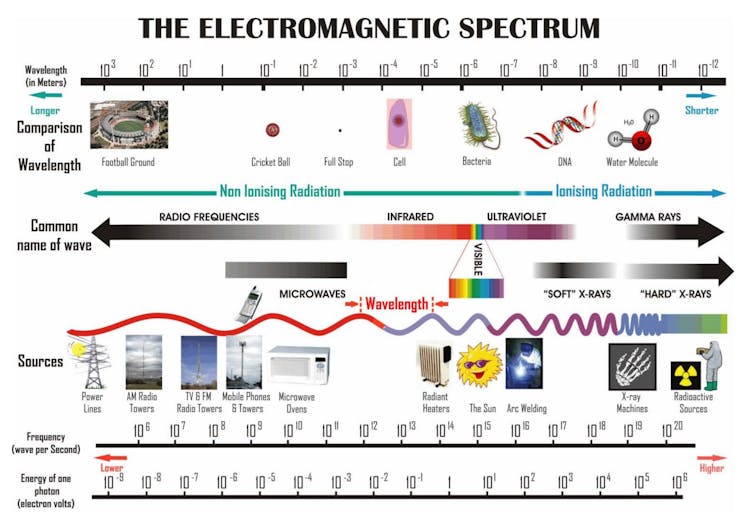

The difference between 5G and previous generations of mobile services (4G, 3G) is that the latter uses lower radio frequencies (in the 6 gigahertz range), whereas 5G uses frequencies in the 30–300 gigahertz range.

In the 30-300 gigahertz range, there’s not enough energy to break chemical bonds or remove electrons when in contact with human tissue. Thus, this range is referred to as “non-ionising” electromagnetic radiation.

It’s approved by the federal government’s Australian Radiation Protection and Nuclear Safety Agency as not having the negative health effects of more intense radiation.

Read more: There’s no evidence 5G is going to harm our health, so let’s stop worrying about it

Radiation can come into contact with the skin, for example, when we put a 5G mobile to our ear to make a call. This is when we’re most exposed to non-ionising radiation. But this exposure is well below the recommended safety level.

5G radiation can’t penetrate skin, or allow a virus to penetrate skin. There is no evidence 5G radio frequencies cause or exacerbate the spread of the coronavirus.

Also, the protein shell of the virus is incapable of hijacking 5G radio signals. This is because radiation and viruses exist in different forms that do not interact. One is a biological phenomenon and the other exists on the electromagnetic spectrum.

5G radio waves are called millimetre waves, because their wavelength is measured in millimetres. Because these waves are short, 5G cell towers need to be relatively close together – about 250 metres apart. They are organised as a collection of small cells (a cell is an area covered by radio signals).

For 5G to cover a larger geographic area, more base stations are needed in comparison to 4G. This increase in the number of base stations, and their proximity to humans, is one factor that may stir unfounded fears about 5G’s potential health impacts.

Your phone may be dangerous, but its radiation isn’t

COVID-19 spreads through small droplets released from the nose or mouth of an infected person when they cough, spit, sneeze, talk or exhale. Transmission occurs when the droplets come into contact with the nose, eyes or mouth of a healthy person.

So if an infectious person speaks through a phone held near their mouth, enough infectious droplets may land on its surface to make it capable of spreading the virus. This is why it’s not advisable to share mobiles during a pandemic. You should also regularly disinfect your mobile.

Read more: Can I get coronavirus from mail or package deliveries? Should I disinfect my phone?

Why are we having this discussion?

To many of us, it’s obvious a human virus can’t spread via radio signals, and such a conspiracy may be linked to a wider distrust of the government in general.

Addressing this myth is critical as property is now being damaged, and individuals attacked. Physical and verbal threats to broadband engineers can be added to a long list of assaults on health workers.

At a time when millions are relying on fast internet to work and study from home, vital telecommunications infrastructure is at risk of being destroyed. Conspiracy theories have motivated arson attacks on 5G towers in Belfast, Liverpool and Birmingham.

Youtube has announced it will devote resources to removing content linking 5G technology to COVID-19.

The announcement came after fingers were pointed at one video, published on March 18 (and viewed more than 668,000 times), in which an American doctor claims incorrectly that Africa is less affected by COVID-19 because it’s not a 5G region. The video remained online at the time of publishing this article.

Stanley Shanapinda, Research Fellow, La Trobe University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.